I'm not much of a dancer. I don't like dancing and I'm not much good at it. So I often find myself on the sidelines of the dance floor, watching rather than joining. The dance pace at a Chassidic wedding is intense but the selection is pretty much standard: the hora, the hora and yet another version of the hora.

Actually, when you think of it, the hora fits the marital theme. Dancers stand in close proximity, hold hands, and dance in a tightly-knit circle. Can you ask for a better wedding metaphor? The newlyweds also hope to live at close quarters, hold hands, and maintain an egalitarian relationship. The circle represents perfect equality as it has no beginning or end, no head or tail, no top or bottom.

An Inspired Dance

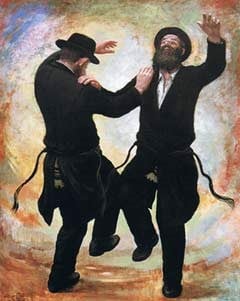

The hora is indeed a beautiful dance but I was once at a wedding where a much more inspired dance was performed. The dance floor was circling with various styles of the hora when two young Chassidim squared off before the groom and began an intricate yet soulful dance. I don't know the name of this wonderful dance but for the purposes of this essay I have named it the inspired dance.

The dance floor emptied as everyone paused to enjoy the spectacle. The dancers faced each other at a distance but acknowledged each other with a bow. The dance began as they slowly circled each other, alternately facing towards and away from each other. Animatedly angling back and forth, they alternated between drawing closer and pulling away.

To me, the choreographed steps told an exquisite tale of two people who yearned for each other but were not yet ready to reach out. The dancers hesitantly surrendered to their yearning but then quickly pulled back. They drew closer again only to pull back once more. They weren't ready yet, there was still so much to explore about each other and about themselves. Reluctantly, they pulled away and gazed from a distance.

As the dance progressed so did the pace. The dancers wound their way across the floor, advancing and falling back, drawing each time progressively closer. They twisted and turned, barely avoiding each other, nearly colliding in their quest for mutual closeness. The dance wound to an end and the dancers reached their peak. They finally approached each other and engaged in a hesitant but warm embrace. The dancers exulted and the spectators applauded celebrating the triumph of happiness.

Siblings and Spouses

The drama that played itself out on the dance floor told a story that echoes across the journey of married life. Marriage requires enthusiasm, commitment and, above all, continuous labor. It is a never-ending process of drawing together, but also a never-ending challenge of overcoming obstacles. After all, marriage brings together a man and a woman, each with natures and characters from the opposite streams of life.

Loving unity between spouses is not constant, is never steady. It is a dynamic energy that thrives on being in a constant state of flux. It flares and fades and then flares up again even stronger than before. Like the inspired dance, it rises and falls, peaks and dips, advances and retreats. The hora, on the other hand, maintains a steady pace of close contact with very little drama. There is no fanfare and no triumph, just a steady pace symbolic more of the relationship between siblings than that of husband and wife.

Siblings play out their own little dance. It is not passionate and bold but natural and easy. What's more, it lasts forever. A married couple must work hard to achieve their loving bond, and once achieved, there is no guarantee of permanence. It might erupt in explosive passion or fade away on the dying embers of broken love.

The inspired dance is creative and dramatic; the hora is natural and predictable. The question we must ask ourselves is, with whom shall we dance the hora and with whom the inspired dance? This is also the question we must ask ourselves as Jews. Which of these two do we dance with G‑d?

The Jew and G‑d

The proper answer is, both. King Solomon employs both metaphors in Song of Songs, when he describes G‑d meeting with us: ""I have come to My garden, My sister the bride" (Song of Songs 5:1).

G‑d and people are as distant as infinity is from the finite. He is the Creator and we are the merely created. In this sense our dance is the square dance; we reach across this gulf and struggle to achieve and then maintain a connection. Yet at the same time, G‑d's bond with us pierces the core of our essence. Even the assimilated Jew, even the apostate, cannot cease being a Jew. On the deepest level, we are claimed by G‑d. Like a sibling who cannot sue for divorce, our dance is the hora, forever together, in an eternal circle that grips us in tight embrace.

Indeed, the Jewish people are metaphorically referred to in the Torah as the bride of G‑d. Endearing as this term is, it doesn't promise an eternal connection. Brides are passionate and loving. But even marriage doesn't promise eternal devotion, as may be seen when couples sue for divorce. Torah grants the Jew another title. In addition to G‑d's bride we are also G‑d's sister. The sibling relationship that we share with G‑d ensures an immutable lasting connection that can never be severed.

Every Jew is a sister and a bride. We, the accomplished dancers, are proficient in the intricate steps of both dances, the hora and the inspired.1

Two Souls

This bride/sister duality, this dual dance we play out with G‑d, is the role of every Jew. G‑d grants the Jew a G‑dly soul and an animal soul. The G‑dly soul is a veritable part of G‑d Himself clothed in the garment of the human body. As we walk, think and talk, we carry a fragment of our Creator in our person. It comprises the essence of who we are, and we cannot surrender it or divorce ourselves from it.

The animal soul is the conventional soul of man, which exists to a lesser degree in all living organisms. The animal soul feels no natural kinship with its creator. It is not inherently holy. On the contrary—its initial attraction is to the worldly. This animal soul must be slowly nurtured with loving care if it is ever to develop a relationship with G‑d.

Given the correct dynamics, our animal soul can learn to connect with G‑d. But its connection cannot be spontaneous or permanent. While connected, it will be fiercely drawn to G‑dliness. It will covet all things holy and enjoy a spectacularly rousing love. But this connection is by no means assured. It can fade as quickly as it rises. It requires constant tending.

Our animal soul is (or has the potential to be) G‑d's bride. The bride prefers the inspired dance, where a powerful connection is possible but requires constant effort and emotional investment. Our G‑dly soul is G‑d's metaphoric sister. The sister prefers the hora, always connected and always dependable.

Some Jews are more devout than others and some are more impassioned than others; but no Jew is more connected to G‑d than another. The G‑dly soul of even the most assimilated Jew remains eternally linked with G‑d. Even after long periods of separation G‑d connects with His sister with familiarity and ease.

Anything for My Sister

The Torah teaches that a priest may not defile himself by attending funerals (thus coming in contact with the dead and contracting their state of impurity). The Torah does, however, offer special dispensation for immediate relatives. A number of relatives are included in this dispensation but the Torah pays the most attention to the priest's unmarried sister. "And to his virgin sister who is close to him, who has been wed to no man, to her shall he contaminate himself" (Leviticus 21:3).2

Metaphorically speaking, this verse may also refer to the relationship between G‑d and ourselves. As we have established, the Jewish people are not only the divine bride but also sister. We, the sister, are close to G‑d and we have given ourselves to no other man.3

The priest may contaminate himself for his sister. G‑d, the greatest "priest" of all,4 may and does enter the life of each Jew, the righteous and the not so righteous, those who dance passionately with G‑d and those who have allowed their passion to fade, even though this entry brings G‑d into the center of our spiritually contaminated lives.5

Why does G‑d enter the contaminated center of our lives? Because the Jew is G‑d's sister. Even with faded passion, we are still on the dance floor and that speaks volumes of our intrinsic connection. We may be saturated with impure thoughts and unholy behaviors but deep within our intimate core, we dance an unending hora with G‑d.

G‑d enters the spiritual mess we have made of our lives because we are inherently related to G‑d. Our house may be in shambles, our rooms a mess, but G‑d feels at home with us. After all, we're family.6

Join the Discussion